Bureaucracy Versus Humanocracy

In Humanocracy: Creating Organizations as Amazing as the People Inside Them (2020), Gary Hamel, an American management consultant considered one of the world’s most iconoclastic business thinkers, makes the case for distinguishing between bureaucracy (the features of which are stratification, specialization, formalization, and routinization, which undermine resilience, innovation, and engagement) and humanocracy (whose tenets are ownership, markets, meritocracy, community, and reinventing management, a system which not only requires new tools and methods, but also entirely new principles). According to Hamel, if we free the human spirit from the shackles of bureaucracy, it will produce profound benefits for individuals, companies, economies, and societies.

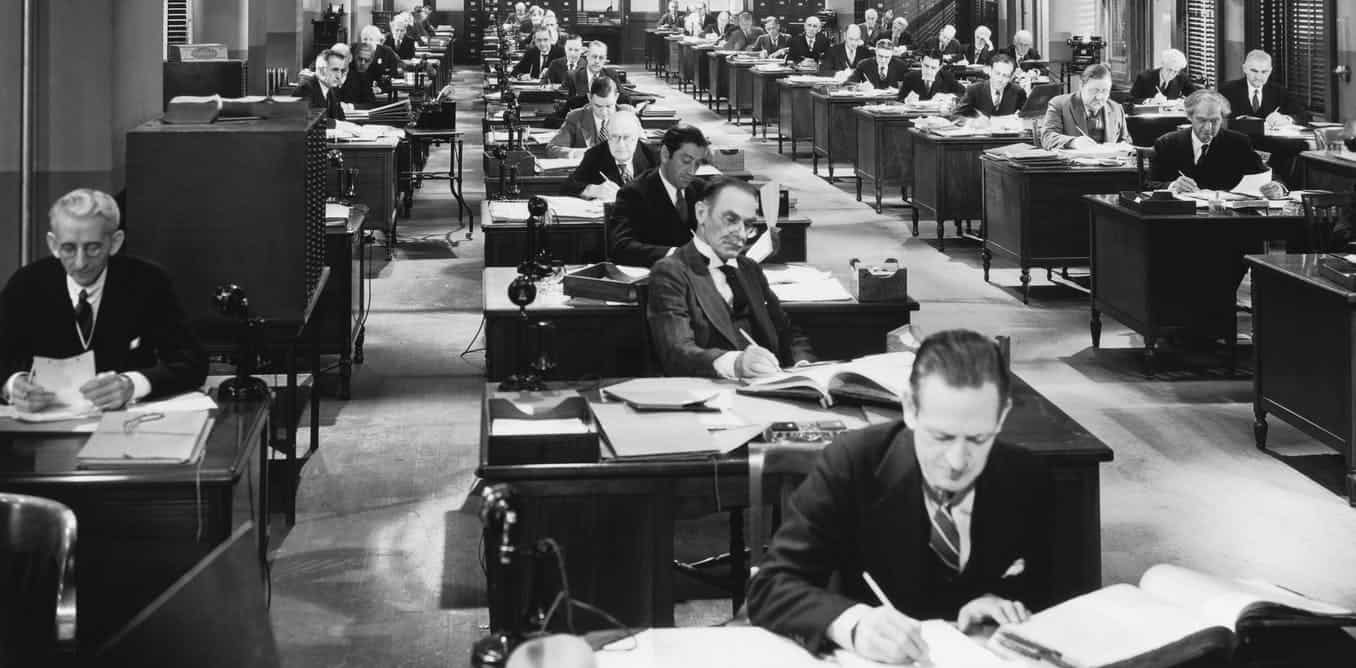

Hamel explains that the word bureaucratic was coined in the early 18th Century by Jean-Claude Marie Vincent, a French government minister. Translated as “the rule of desks,” the label was not intended as a compliment. Vincent viewed France’s vast administrative apparatus as a threat to the spirit of enterprise. A century later in 1837, the British philosopher John Stuart Mill described bureaucracy as a vast tyrannical network, while German sociologist Max Weber touted bureaucracy as superior to any other organizational form in precision, reliability, and stringency of its discipline.

Bureaucratic organizations are inertial, incremental, and dispiriting, says Hamel, in an Internet article by Jay Robb, McMaster University professor. In a bureaucracy, Hamel goes on to say, the power to initiate change is vested in a few senior leaders. Worst of all, bureaucracies are soul crushing. Deprived of any real influence, coworkers disconnect emotionally from work. Initiative, creativity, and daring – requisites for success in the creative economy – often get left at home. Bureaucratic organizations have timid goals, shun risk-taking, lumber along at a plodding speed, repress creativity, cramp autonomy, punish non-conformity, and in return get tepid commitment from disengaged coworkers.

By comparison, a humanocracy optimizes everyone’s contribution. Companies become as resilient, creative, innovative, adaptive, entrepreneurial, and energetic as the people who work in them. Rather than deskilling work, coworkers need to be upskilled. In his book, Hamel profiles humanocracy pioneers like U.S. steelmaker Nucor and the Chinese company Haier, the world’s largest appliance maker. These big companies show that it is possible to have the benefits of bureaucracy – control, consistency, and coordination – without the crippling costs of inflexibility, mediocrity, and apathy. The experiences of the post-bureaucratic rebels testify to a single luminous truth: an organization has little to fear from the future or its competitors when it is brimming with self-managing micropreneurs.

Freeing our team members’ and leaders’ spirits – that is the promise of humanocracy. With grit and determination, we can claim that promise for ourselves and our organization, says Hamel. Like every epic quest, the journey will be arduous but ultimately fulfilling. It will test us but will also feed our souls.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

Vice President Emeritus for Learning Technologies Donald Smith, Ed.D, CPT, headed ME&A programs in learning, leadership, and performance enhancement. He stayed with the firm in his retirement, bringing more than 65 years of experience as a coach, designer, facilitator, evaluator, manager, educator, and organizational change architect in more than 40 countries. He is affectionately known as ME&A’s MENCH.